In this week’s episode of the SisterWild podcast, Heather Rivera shares her story of life after leaving the Worldwide Church of God, the now defunct religious sect that Rebecca and I also grew up in. In it, she brings up an issue that many of us face: how do we introduce our post-transition selves? How do we talk to others about our journeys, but on our own terms and without revealing more than we are comfortable with?

Heather says:

What has happened to me has been so profound and destructive. I still struggle with it a little bit…when someone’s like, “Hey, tell me about yourself?” And I don’t even know where to begin sometimes - there’s so much. So, when they ask me about myself, I’m like, “Well, I’ve lived a lot of lives.”

I get what she’s talking about. You don’t want to dump your entire life story on some poor guy at a dinner party who’s just trying to engage you in a little small talk. “How did you meet your husband?” for example, is a perfectly normal question that that perfectly normal people ask when they want to get to know you. It’s fair game. Still, it’s questions like these that give me a knot in my stomach.

For example, what I do NOT say in response to this question is: “Oh, we were married in a cult when I was 19 years old. We left together the day after the wedding. But don’t worry! The group doesn’t exist anymore. Anyway! How about this weather? It’s not the heat, it’s the humidity, am I right!?”

Over the years, I’ve been able to refine my answer, aiming for something that doesn’t shut down the conversation and, at the same time, isn’t an uncalled-for HBO special.

Usually, I say something like this: “We met through the church we grew up in.” If I want to reveal a little more – to give a bit of a more specific picture without too much detail – I might say. “We met through church. Our families were very religious and so we got married pretty young. We’ve been together a long time!”

Here is another example of the kind of thing I do NOT recommend saying in response to a get-to-know-you question from someone you’ve just met.

Question: Are you going home for Christmas?

What you should NOT say: Christmas? Well, I was raised in a controversial new religious movement called The Worldwide Church of God that rejected modern Christian holidays as evil. The Branch Davidians of Waco infamy are our religious cousins. Our founder, Herbert Armstrong, was an ad man from Iowa who believed himself to be God’s end-time prophet. He told us that we needed to follow many of the laws outlined in the Hebrew scriptures like the Saturday Sabbath, holy days, and dietary restrictions. We were God’s one true church. We were pacifists. We didn’t vote. We were suspicious of modern medicine and processed foods.

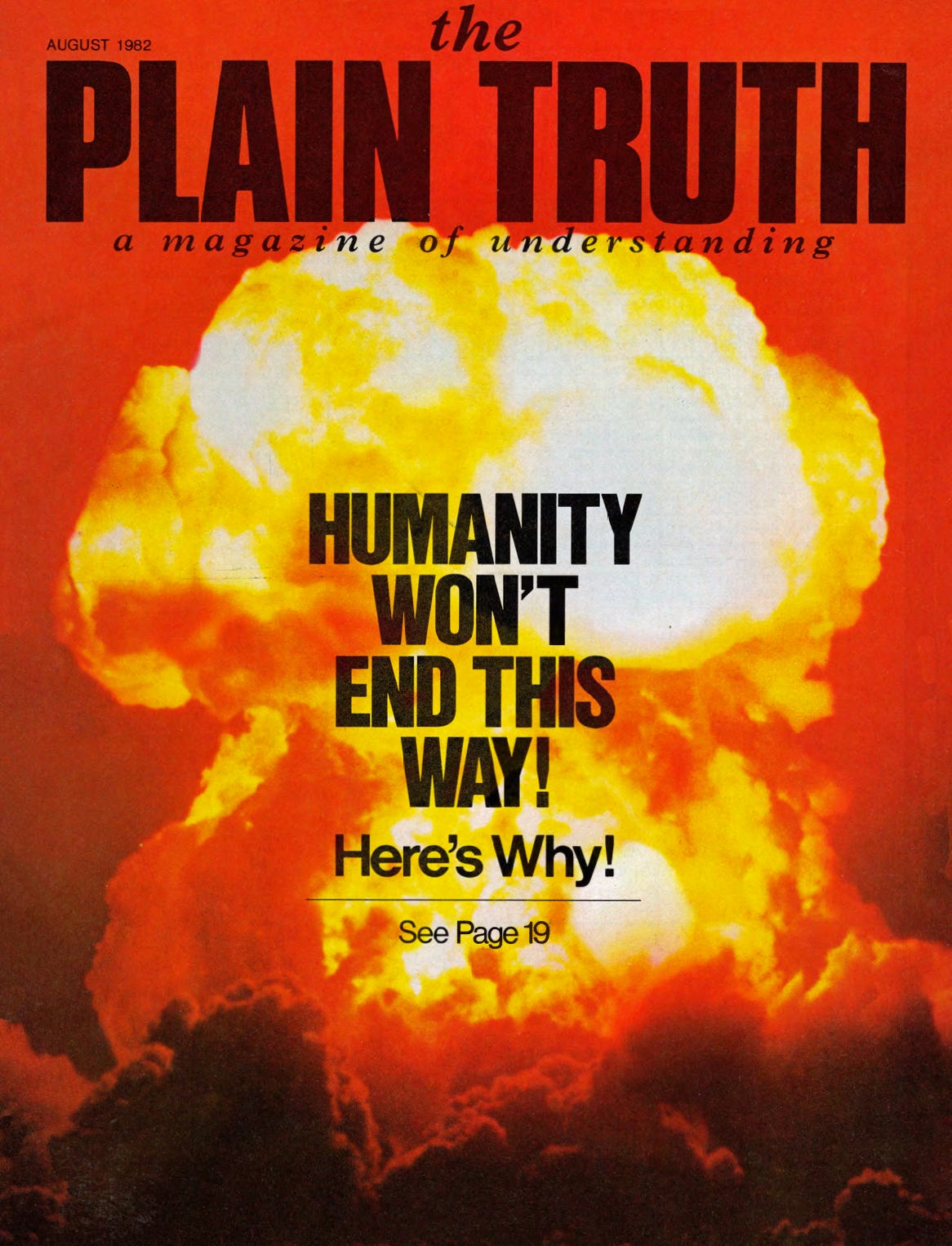

Armstrong taught that humanity would eventually destroy itself through war and environmental disaster (a perspective I still find quite believable). Prior to all this destruction, however, WCG members would be whisked away to what we called the Place of Safety. We needed to be ready at any moment to flee. I remember one time I was very young and my father called me from another room. I didn’t hear, (or perhaps “didn’t hear” as children do). My father said sternly, “You need to come when I call you. What if I was calling you to leave for the Place of Safety?”

You think that would make me feel terrified. Honestly, it didn’t, but it did make me very good at coming when I was called. Instead, I was utterly captivated by the Place of Safety, rumoured unofficially to be in Petra, Jordan.

I was also obsessively reading and re-reading Little House on the Prairie at the time, and I think the two ideas co-mingled in my mind. My young imagination pictured us in the caves of a Middle Eastern desert in American pioneer garb, waiting out Armageddon. Why we would suddenly be in long skirts and bonnets, I have no idea, but that is how I pictured the purported three-and-a-half years we would spend safely tucked away from World War III.

I was taught that, at the last moment, just as humanity was about to destroy itself totally, God would intervene to prevent the complete destruction of the Earth and usher in a Utopia, which we called The World Tomorrow or The Kingdom of God. Rather than spending eternity in heaven, as Christians believe, we would live out eternity here on a renewed Earth, where there would be no more death or war or disease or trouble of any kind.

The WCG has been variously called a sect, a dooms-day cult, a new religious movement, a high demand religion, and a scam. To the Jews we were a joke – a bastardization. To the Christians we were a cult. Despite this, and despite my exceedingly mixed feelings about the group and my time in it, I continue to recognize it as a foundational part of who I am. For better or worse, the WCG will always feel like my home.

I was born in 1985 near Pasadena, California which, at the time, was the WCG’s headquarters. My parents met and married at Ambassador College, Armstrong’s unaccredited Bible college that taught his unique theology, where they continued to work for the church after graduating. I was an infant when Armstrong died in 1986. Shortly after this, my family moved to rural Montana where I was raised along with my four younger siblings.

My childhood in the WCG was largely a positive experience. Indeed, my main source of stress was the reaction of others to my religious beliefs and practices. I was sent to public school but, at the same time, it was made very clear to me that my main source of identity was in the WCG. When I was with children who were not in The Church (as we phrased it), I felt a sense of specialness and separateness that was at times inhibiting and at times empowering. I understood that there was something fundamentally different about me. For the most part, I do not recall this being distressing, at least, not when I was very young. It did take energy and effort, however, to maintain my social and spiritual distance from others.

It's here that what may otherwise be the story of an odd and ephemeral religious group takes an unusual turn. Groups that scholars call new religious movements (NRMs) come and go with little fanfare; most don’t make the news. But beginning in the mid 1990s, the WCG went through radical doctrinal and cultural changes that moved us towards mainstream Evangelicalism. Barrett (2013) explains how, in a sudden and devastating proclamation, church leadership “announced that the Worldwide Church of God had renounced all of its founder’s distinctive teachings and had become a straightforward Evangelical Christian church” (p. 4).

I was nine years old when Armstrong’s successor, Tkach Sr. announced the move to Evangelicalism. I remember watching the infamous sermon, which had been distributed to all the local congregations on VHS tape and played during a January Sabbath service, and seeing the adult members around me react with shock, confusion, even tears.

(By the way, one of the nice things about being raised in a cult/ new religious movement is that sociologists will study you and write books about you, which is very handy.)

Detailing the theological changes here isn’t important; plenty of others have done that. What is important is the impact this upheaval had on my family and my community. This experience has had a profound impact on the deepest parts of my life in way that I often find difficult to explain.

As the changes in the WCG began to take hold and I moved towards adolescence, I became hyper aware of the social and theological issues that were rocking my world. I became a theologically obsessed adolescent. Even in grades five and six I remember pouring over church literature and my father’s vast collection of religious books. I don’t remember doing this with anxiety, but, instead, great interest and fascination.

To say that such sweeping and sudden doctrinal changes towards mainstream orthodoxy is unusual would be an understatement. Indeed, there is no equivalent that I am aware of in modern religious history.

It was also during this time that I became aware that I was not religious in the right way. Indeed, a number of children and their families in our mostly Evangelical rural community took it upon themselves to “save” me, which I found quite distressing.

To me, the theology and culture of my mainstream Christian peers was terrifying. How could anyone worship a god who would send someone to hell for all eternity? How could someone think that this god would punish someone imply because they had the misfortune of never having met a missionary and converting to their brand of Christianity? Further, why would that god snatch people up to heaven in some sort of “Rapture? and abandon the Earth that he created? My list could go on but, suffice to say, I came to the speedy conclusion that I should keep well away from these Evangelicals and their dangerous and unusual beliefs.

My adolescence was tumultuous. My parents were among those who continued to attend the WCG while adhering to Mr. Armstrong’s original doctrines The turmoil in the church caused a great deal of social, familial, and emotional strife and, combined with the expected adolescent boundary-pushing, this created a lot of tension and conflict. Much of this had to do with my teenage sexual exploration, which was strictly controlled.

It had always been my plan – my dream – to join the Young Ambassadors at Ambassador College.

I had spent countless hours flipping through my parents old college envoys with gleaming photos of students from past years. The Pasadena campus, with its beautifully manicured lawns, concert halls, palm trees, and endless sunshine was everything I was hoping for. It wasn’t just an escape from Montana; it felt like the place where belonged, finally part of the majority, with other people like me.

But by the time I was 18 the church was dwindling away. Ambassador College had been shuttered, leaving the question of what to do with me after high school.

Certainly, I could not be sent to a secular college to be polluted with evolution, lesbianism, socialism, free-love, and abortion. So, a compromise was made and I went to Trinity Western University (TWU), an Evangelical university in British Columbia where, at least, some kind of moral standards would be upheld, even if the culture was not specifically ours. The selection of this particular school was largely engineered by me so I could be near a young man I was involved with at the time. Dan was also raised in Worldwide and he and I had met at one of our annual festivals, the Feast of Tabernacles. (Some might recognize this as Sukkot).

Trinity Western was my first real experience of the wider world and Langley, BC seemed like a bustling metropolis compared to rural Montana. A deeply Evangelical university, many of my classmates had gone to private Christian high-schools and seemed at ease in the shared culture of contemporary Evangelicalism.

TWU did not work for me. Every Friday, Dan would pick me up and take me to his family’s home, in part so we could attend Sabbath services. I enjoyed the weekend escape and found myself devastated to return to my dorm on Sunday evening. In the end, I would spend only one year at Trinity Western. My poor academic performance was compounded by being completely disoriented by university life. Believe it or not, the lacklustre school system in my isolated town combined with my cloistered religious upbringing had left me wholly unprepared for a post-secondary education. I had never taken exams. I did not know how to write a basic essay. I didn’t know that you needed textbooks. Having no money, and no one to ask for money, I simply went without textbooks. You can see how this might cause problems.

After one year of private university that I had no money for in the first place, I dropped out.

Dan and I married two months later. We moved to Toronto the day after the wedding. Though I do not think that either of us consciously thought that we were moving to put distance between ourselves and the WCG, the idea that we might be somewhere where nobody knew us and we had no church connections was certainly tantalizing and liberating. After our move, with no discussion, we simply had no more contact with the WCG.

I consider this move to Toronto to be my exit from the Worldwide Church of God but certainly not my exit from religion. For some time, I felt sure that there must be some church that was “true” and if only I could study the Bible hard enough, I would figure out which one it was. My anxiety over not being able to find the theological and philosophical answers I was looking for was devastating and, in some ways, humiliating. I felt ashamed; like I was failing some sort of test. I began to obsessively ruminate over what I thought were my “sins” and the fact that I could not figure out what church I needed to join or what I needed to do to be right with God.

In addition, I was 19 and married, had no money or social supports, and had recently moved to one of the largest cities in North America after only ever experiencing rural life.

I ended up attending community college to study child and youth care. Childcare, I felt, was something I knew how to do, and, at that point, it would not have occurred to me to pursue much else. Socially, however, I felt out of sync with my peers, none of whom needed to go home at the end of the school day to make dinner for their husbands and who seemed blithely untroubled by the state of their souls.

During this time, I ended up joining the Anglican Church because of a friend. Since the collapse of the WCG I had no ritual or routine in my life and I missed it. There was no Sabbath, no holiness, no sacred space or time in my life. Anglicanism did not feel like my home, but it was a nice place to visit. I liked the Anglicans. As far as I could tell, they could not agree on anything, yet they showed up week to week made themselves a community. They also had no pretence about being the one, true church. I found this comforting. While it has now been many years since I left the Anglican church, I still consider it to have been a safe and healing experience

In the end, I came to realize, with a lot of sorrow, that I probably did not believe in the god of the Bible, or any other god, and so I left church life all together. Because I was working for an Anglican parish at the time, this also meant losing my employment. I felt an obligation to keep my loss of faith and belief private so I didn’t distress others in the congregation, and I quietly disentangled myself from church life without alerting anyone to my personal crisis.

There’s a lot more to it, but that’s the sad and short version.

I had lost the religious tradition of my childhood and now, despite my great efforts, I had lost my belief in god too. My lack of belief isolated me from the kinds of communities I felt were so important. I hated the label atheist and felt it did not capture what I truly felt or believed. But if you are not a believer, then, as far as I understood, atheist was the only category left for you. Either you had faith, or you did not. Either you were in or you were out.

At this point at our imaginary cocktail party I would sip my drink and pause. I know my conversation partner would want me to tie things up with a nice ending. I know what I’m supposed to say. I’m supposed to say that life is better now, that I’ve figured things out, that I’m so grateful to be “free” after being in that terrible cult.

The reality is, I’m not so sure.

I wouldn’t RECOMMEND a childhood in the WCG. At same time, I still find mainstream Christian theology much more frightening.

And I never quite got over this idea of the Kingdom of God, a world where there is justice, hope, and reconciliation. Escaping the Earth to become an angel in heaven never had any appeal to me, which is probably why I failed at being a Christian.

All of life is about going away and coming home again. And we all, in one way or another, learn that we can’t. Really, that’s what growing up is about.

Even if I can’t go to my WCG home I still carry pieces of it with me. Memories of travelling for days to meet friends for our yearly festivals. Hanging out in the hallway with the only Jehovah’s Witness kid in the school while we waited for our class to finish the Halloween party. Visiting Ambassador Auditorium for the first time and feeling like it was my own.

And, most of all, the idea that we can work towards a just and peaceful future on Earth, which was probably the most controversial and ridiculous of all our ridiculous beliefs.

Despite my loss of belief, I still have faith.

So, no. I probably won’t be going home for Christmas.

But thank you for asking.

Jessica Pratezina is one of the co-founders of SisterWild, a community for women in religious transition of all kinds. She is a writer and researcher who studies religion, gender, and life-writing. She lives in Toronto, Ontario. She can be reached at thesisterwild@gmail.com