My brother Matt hadn’t seen our oldest sister Audrey in twenty-three years. Glorianna, his current wife, called me early one morning in the spring of 2023. She said that he had been thinking about Audrey and was sad that he hadn’t seen her in so long. He wanted to visit her to see how she was doing and make sure she was okay. It was a busy time of year for me, and I asked if we could set up a time to meet in the summer when I could take more time off work, but Glorianna was four months pregnant with her twelfth child and was due in August. Their oldest daughter was also due with her second child in June. With the new babies arriving, she and Matt wouldn’t have the time to drive all the way to Central California, where Audrey lives in an adult foster care home. Matt and Glorianna lived in Colonia LeBaron, a small fundamentalist Mormon community my father’s family had founded in northern Mexico in the 1940s and the farming town Audrey, Matt, and I grew up in. I would be flying in from Portland, Oregon, with my husband, Alan.

Audrey is the oldest of Mom’s ten kids. Four years older than me and eighteen months older than Matt, she was much taller and stronger than we were. She used to rock back and forth in her chair, pick at the edges of her blouses until the threads were shredded apart, and have violent outbursts that terrified me. When she clenched her pink hands together and her knuckles turned white, I knew I needed to quickly move away from her so that she wouldn’t grab my hair or pinch my arms.

After many years of struggling, when Audrey was fourteen, Mom placed her in a mental institution in the States close to where Mom’s parents lived in Central California. Audrey later moved in and out of small foster care homes in the same area, and my family and I visited her when we could.

Mom died unexpectedly from a tragic accident on our farm in the colony in 1987, which changed the trajectory of the life I had expected for myself at the age of fifteen. Matt and I took our younger sisters and escaped our abusive stepfather and his family. Matt ended up eventually returning to the colony and continued living his life according to the fundamentalist beliefs Mom had wholeheartedly embraced. After my youngest siblings and I lived with our grandmother for four years, I ended up raising them on my own in Oregon while I put myself through college to become a teacher.

Over the decades, Matt and I grew apart in almost every way, especially regarding our spiritual beliefs. In recent years, arguments about religion had transitioned into arguments about politics, social issues, and cultural norms. We are at opposite ends of the spectrum. My life experiences drove me away from organized religion, while his life became completely enveloped by it. He married twice and divorced once while I remained single. I didn’t marry Alan until I was thirty-seven, not long after my sisters had moved out and started their own lives.

Matt still believed that practicing any kind of birth control was a major sin against God. When I told him I didn’t want to have my own children, his face looked so shocked it was like I had physically punched him. That’s just one of the many examples of disagreements we had that strained our relationship. The early childhood trauma that had bonded our deep connection had transitioned to a solid wall of contempt. We were so far apart that we couldn’t find a common meeting place between us. We didn’t see each other as often as we used to and rarely talked on the phone. When we did, conversations were superficial. Before Glorianna called me that spring morning, I hadn’t seen him in two years.

I had remained in touch with Audrey and her many caretakers and learned that her official diagnoses are bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, both mental illnesses that are common on our father’s side of the family. Audrey had lived in her current foster home for a decade, and I had visited her there a few times. I called her house manager after I talked to Glorianna to see if Audrey would be home on the only weekend in April that Alan and I were available to travel. She would be, and we could see her, but we needed to meet with her outside her home. The house manager didn’t want us to disrupt Audrey’s housemates’ routines. We set up a time to get together at the Black Bear Café on a Sunday morning in Visalia.

The four of us had met for dinner the night before our visit, and Matt and I admitted that we were both nervous about seeing Audrey. Even though the three of us siblings were now in our fifties, there was a part of me that was still a little afraid of her.

The bright California sun was warmer than I remembered the day we saw Audrey, but it was a welcome feeling compared to the cold, rainy season in Portland. When we pulled into the restaurant parking lot, Audrey and her caretaker were waiting for us next to a wooden sculpture of a giant black bear in front of the restaurant. Audrey rocked back and forth from her left foot to her right, like she might also be nervous. She wore a tan cardigan with leopard print and fitted jeans. Her brown hair was cut short in layers, and her bangs were pinned back with a matching barrette. She looked younger - all dressed up and stylish. She saw us and smiled at me but looked away from Matt like she didn’t know who he was. She was still missing her two front teeth, but my sister’s eyes looked more alert than they had the last time I saw her.

After Camille introduced herself, I asked if I could hug Audrey, and she said, “Audrey likes hugs,” and laughed lightly like she was surprised by the question.

“Audrey used to not want us to touch her,” I explained a little more defensively than I meant to, feeling a little bit of sister-guilt for not realizing she had changed in a substantial way.

“Well, I just love Audrey!” Camille was enthusiastic and friendly and had a glowing smile. It was obvious that she was happy that we had come to visit our sister. “She’s my girl, and I just love her,” she said as she gave Audrey a warm one-arm embrace.

“I want burgers and fries now,” Audrey said in her monotone voice. My sister didn’t initiate conversation unless it was to ask for food, especially burgers and fries and anything sweet. They were always her favorites.

Matt gave Audrey a light hug, but she still didn’t seem to recognize him. As we waited for our table at the front of the restaurant, Matt sat on a bench at a corner of the busy café, dropped his flushed face into his hands, and sobbed. I hadn’t expected him to cry but related to the years of sadness he seemed to be releasing, letting go of something he had held onto deep inside himself for too long. The animosity I had felt for my preachy brother melted a little, and his humanity shined through in a way that gave our disagreements less meaning.

Matt’s face was still red when he and Audrey sat next to each other across from me. Everyone but Audrey ordered traditional breakfasts, and Matt asked Audrey what song she wanted to listen to on his phone. “Country Roads,” she said. Matt set his phone on the table between them. Despite the sound of others’ conversations all around us, he leaned in close to her. Their shoulders touched as they listened to the tiny phone’s speaker play Take Me Home, Country Roads by John Denver.

“It’s her favorite song,” Camille said loud enough for the people at our table to hear. Camille had been one of her caretakers for the past few years and seemed to know her well. “Whenever I ask her what she wants to listen to, she says John Denver, and we play his greatest hits,” she said, shaking her head. “She never wants to listen to anything else. John Denver all day long. Isn’t that right, Pretty Audrey?”

“Yes. I like John Denver,” Audrey responded.

Camille’s comment didn’t surprise me. I still liked listening to John Denver. His songs took me back to our childhood home on the farm in Colonia LeBaron, where Audrey, Matt, and I grew up surrounded by dirt and gravel roads, pecan and peach orchards, and alfalfa fields. I was eight years old when we finally had electricity in our little adobe house, and Mom pulled out an old record player and played his greatest hits on repeat. The colony was in a valley, and we weren’t able to receive good radio connections or TV reception. John Denver’s Greatest Hits were like a soundtrack to our childhood.

Camille continued to catch us up on how Audrey had been doing. She explained that they lowered her stronger medications and that her doctors didn’t think she needed them anymore. Audrey had become much more responsive. I could tell by Audrey’s facial expressions that she was more vibrant and aware. “We have to watch her closely to make sure she’s eating when she’s supposed to. We make sure she stays hydrated, too. That seems to help her stay balanced and less irritated.”

“Has she had any violent outbursts?” I asked, feeling more at ease now that we were all sitting together and realizing that Audrey was doing better than I had seen her in decades.

“Not really,” Camille said, “but she’s definitely been more ornery.” She looked at Audrey. “But we sure love her. Don’t we, Pretty Audrey? We sure do love you!” Audrey smiled and nodded, and I couldn’t help but feel joy for my sister. The tenderness and care that was being expressed on her behalf uplifted me. It also made me feel sad for Audrey and the childhood she and I had left behind.

Audrey didn’t have an official diagnosis when we were kids. We didn’t have the money for good healthcare, and Mom and our severely religious community didn’t know how to handle Audrey with the kind of love I saw being expressed at the breakfast table that morning in California. The rules and expectations in LeBaron didn’t have a place for a child with the kinds of behaviors and needs she had. She didn’t have the ability to follow the normal rules of society, which for girls and women were to do what we were told, help our mothers take care of the household and our younger siblings, and prepare ourselves to become a good wife and sister wife.

Mom and the people in the colony believed that my sister was possessed, that she had been cursed for a choice she made in the preexistence (the spirit life before the one we were living together on earth). Mom was mostly patient with Audrey, but family and other community members thought Mom was too soft, as if her patience and kindness somehow spoiled Audrey. I honestly don’t think Mom knew how to manage her oldest daughter or how to help her.

Some of our closest family members tried to help tame Audrey by taking her in and having her live with them for a while. They believed my sister needed harsh punishment to force her to conform to the way they expected her to behave—deeply held beliefs about raising children that often led to shouting and physical beatings. I was deeply disturbed when I was a little girl watching the way she was treated. I knew there was something wrong with it but always felt powerless to change anything. The memory of it was so heartbreaking that I had to breathe deeply to calm myself and come back to the present moment.

Feeling Camille’s enthusiasm and watching Audrey now, sitting next to Matt and smiling as they listened to John Denver, I felt a surge of hope. Despite the trauma and the years of separation, here we were—together again. Our paths had diverged in so many ways, yet the love we shared as siblings remained powerful.

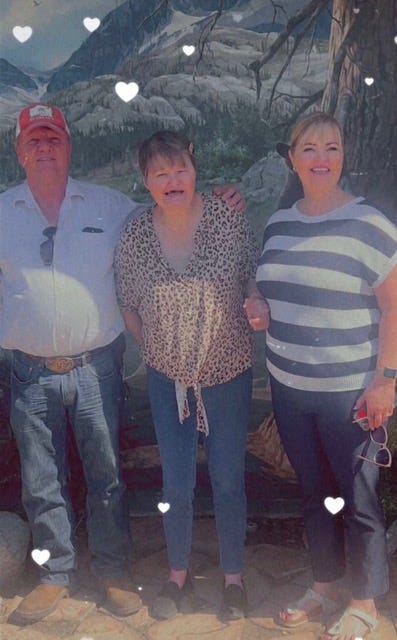

After breakfast, we took photos in front of the restaurant. Audrey stood between Matt and me, holding my hand. It was the first time I remember feeling safe next to her, comfortable with our closeness.

We walked Audrey and Camille back to their van. The sun was getting hotter, casting a warm glow over everything. As we hugged goodbye, Audrey held onto me a little longer than I expected. “I love you, Audrey,” I whispered. She nodded and smiled.

As Alan, Matt, Glorianna and I drove back to the hotel, we reflected on the morning. Matt and I both agreed that Audrey was doing so much better than we had ever imagined. Despite our differences, Matt and I had come together for Audrey, and in doing so, we had found a way to heal some of our own wounds. Family is complicated, messy, and often painful, but our relationship and mutual affection for our sister helped us to find common ground, a place to meet in the middle and agree on something that really mattered to us both. And in the end, maybe that’s enough.

Ruth Wariner is a writer who lives in Portland, OR, and one of the founders of SisterWild. Her book, The Sound of Gravel, chronicles her family’s journey in the fundamentalist Mormon community of Colonia LeBaron, Mexico.

So grateful that Audrey found someone to help her care for her health and mental health. She does look content. It must have been a wonderful day for family 🙏

You're able to describe so clearly the ways in which you and your brother see the world differently. It makes it all the more impactful when you then show how the love you both have for your sister transcend your differences and creates a common bond. Well written and a perspective that lifts my heart.